Tausende Menschen in Ghanas Hauptstadt Accra leben vom westlichen Computerschrott. Sie riskieren Leben und Gesundheit. Eine SZ-Wissen-Reportage.

Was für ein elender Ort. Der Rauch hier ist so dicht und schwarz, dass man das Kind zunächst kaum erkennt. Je näher man ihm kommt, desto mehr tränen die Augen, desto mehr brennt es in der Nase, im Mund und im Rachen. Dann aber sieht man, dass der kleine Junge auf einer Müllkippe sitzt, auf einem Berg voller Glasscherben und Computertrümmern.

Er hustet, schaut kurz auf, dann greift er nach einem kinderkopfgroßen Stein und haut ihn auf den Monitor, der vor ihm liegt. Beim ersten Schlag splittert das Glas, beim zweiten bricht es ein. Und als er den Stein wieder zur Seite legt, fließt dickes, hellrotes Blut aus seiner rechten Hand.

Er wischt sie kurz über die dreckige Hose, dann bricht er die restlichen Scherben aus dem Gehäuse. Kwaku Prince Yeboah heißt der Junge mit der blutenden Hand und dem traurigstarren Blick. Er gehört auf der Mülldeponie hinter dem Agbogbloshie-Markt in Ghanas Hauptstadt Accra schon zu den älteren Kindern, er ist zehn Jahre alt, viele sind auch erst fünf oder sechs.

Blutende Hände sind das kleinste Problem

Sie zerschlagen Computerbildschirme mit Steinen. Schnittwunden haben sie alle, aber das ist das kleinste Problem. Der größte Elektroschrottplatz des westafrikanischen Lands ist eine gigantische Giftmüllhalde, eine, in der sich Konzentrationen von Blei, Kadmium, Barium, Quecksilber, Chrom, Arsen, Beryllium, bromhaltigen Flammschutzmitteln und anderer Giftstoffe wie polychlorierten Biphenylen oder Chlorbenzol finden lassen, die bis zu 100-fach die Normalwerte übersteigen.

Wie viele Kinder und Jugendliche schon erkrankt oder gestorben sind, weiß kein Mensch. Sicher aber ist, dass es diesen Ort nicht gäbe, wenn Exporteure in Europa und Amerika ihren giftigen Computerschrott nicht nach Ghana schicken würden.

Oft deklarieren sie ihre Profitgier als Entwicklungshilfe. Wenn nicht gerade der tiefschwarze Rauch ungezählter Feuerstellen alles verhüllt, dann sieht man die gewaltigen Ausmaße der Deponie. Tausende Menschen leben von ihr.

Ausgeweidete PC-Gehäuse und zersplitterte Bildschirme türmen sich bis zu vier Meter hoch. Der Boden besteht fast nur aus Asche. Überall liegen Kabel herum, zerbrochene Platinen, Tastaturen, Prozessoren, Transformatoren und Hunderte Kothaufen.

Auf Schlammlöchern und Tümpeln treiben Flecken, die grün, orangefarben oder blaumetallisch leuchten. Da die Ziegen- und Kuhherden auf der Müllhalde nichts anderes finden, saufen sie aus grell schimmernden Pfützen und fressen ascheverseuchtes Gras.

So sieht es also aus, wenn Europa und die USA vorgeben, die “digitale Kluft” zwischen der Ersten und der Dritten Welt schließen zu wollen. Rund drei Viertel der Desktops, Laptops, Drucker, Scanner und Kopierer, die als Secondhandware deklariert nach Afrika exportiert werden, sind schlichtweg Elektroschrott.

Jedes Jahr, so schätzt das UN-Umweltprogramm, fallen weltweit 50 Millionen Tonnen des giftigen Mülls an, allein in Deutschland sind es rund eine Million Tonnen. Und die Menge nimmt zu. Dafür sorgen schon die Hersteller mit immer schnelleren Prozessoren, noch größeren Flachbildschirmen und leistungsfähigeren Handys. Mit jeder technischen Neuerung wächst der Elektroschrottberg in Afrika, China und Indien.

http://www.sueddeutsche.de/wissen/ghana-im-hoellenfeuer-der-hightech-welt-1.689901

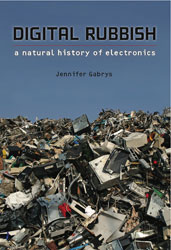

Digital Rubbish: A natural history of electronics by Jennifer Gabrys in the digitalculturebooks series.

Digital Rubbish: A natural history of electronics by Jennifer Gabrys in the digitalculturebooks series.